Canalside is unfinished. Like Benjamin West’s portrait of the American delegation to the 1783 Peace of Paris, the parts that are done are great, but it remains in a sort of perpetual limbo. A recent Buffalo News article underscores how the current “lighter, quicker, cheaper” fetish has left us with a Canalside that fails to live up to its potential as a year-round attraction. The blame for that runs wide and deep, and the project is held back to this day because of it.

To examine Canalside today, we ought to do so within its recent historical context, and the insufferably political one-step-forward, two-steps-back progress on the Inner Harbor. This brings us, inevitably, to Bass Pro.

Like so many things we Buffalonians pay attention to, the Bass Pro story enjoyed quite the arc from hope to joke. When Buffalo Mayor Anthony Masiello and Governor George Pataki ironically donned camouflage and pre-Trump red caps to make the big announce in 2004, fully 12 years ago, Canalside didn’t exist and the whole area was asphalt and weeds.

New Buffalo

In July, Buffalo News columnist and public school opponent Donn Esmonde opined that the “demise of Bass Pro was [the] turning point for New Buffalo“. This is oversimplistic propaganda. Coming from Esmonde in particular, it’s patent narcissism.

First off, there is no consensus on even whether a “new Buffalo” exists, much less when and how it came about; to conclude that it had to do with Bass Pro is absurd. Let’s start with basics: the city of Buffalo’s population continues to shrink. An estimate from May 2015 shows a slowing of the loss of city residents, but a loss nonetheless. Since the 2010 Census, the population has shrunk about 1% per year. By contrast, Erie County’s population grew by a fraction of one percent. The city’s population peaked in 1950 and has been in decline ever since – most dramatically in the 1970s. A lot of that has to do with improved mobility, automation, a shift from regional to global economies and free trade, de-industrialization, and the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway. “Old” Buffalo of rust, decline, shame, and the butt of jokes has been palpably transformed into something that at least feels better, even if the data don’t all agree on objective economic or social improvement.

Unemployment is down, population loss seems to have stabilized, and people feel better about the region than in previous decades. Those of us in the area who have some amount of disposable income exalt in the new restaurants, shops, and startups in town. The #Buffalove is palpable as we witness art installations near the grain elevators, the rejuvenation of our waterfront, Hertel, Grant, and Elmwood are always changing and improving the quality of life for our cognoscenti. But you’re not generally going to have a rennaissance while shrinking. Bass Pro was not the cause of Buffalo’s decline, or its years-long civic and economic depression. It was, at best, a symptom of its time.

When Bass Pro was announced in 2004, there weren’t a lot of blogs. There was no Twitter, no Facebook. There was no real social media to speak of. Only kids used MySpace. That year Buffalo Rising began publishing online and a periodical, devoted to promoting good news about the City of Buffalo. Making Buffalo feel good about itself was a difficult task, but Buffalo Rising was at its forefront, never straying from its narrowly defined mission. Indeed, “New Buffalo” was a term that Buffalo Rising’s Newell Nussbaumer and George Johnson popularized, making it the centerpiece of their effort. As Buffalo Rising focused on economic good news, WNYMedia.net and its array of writers and podcasters focused on a broader range of subjects touching on Buffalo’s suburbs, its neglected and struggling outer neighborhoods, and its diseased political culture.

The turning point for New Buffalo was the adoption of online communication and debate, which later blended into social media. Credit is also due to Old Home Week, Jay Rey’s and Charity Vogel’s “Revitalize Buffalo” series that the Buffalo News published in 2004, and the grassroots offshoot organization that activist Amy Maxwell spearheaded. Not, as Esmonde claims,the rejection of an anchor tenant for Canalside. Esmonde writes,

Any road-to-revival capsulation that credits CEO-laden state agency boards, elected officials (with rare exception), or corporate power-brokers confuses cause with result.

Esmonde then goes on to quote and offer plaudits to Howard Zemsky, a CEO and corporate power-broker who sits on state agency boards. There is very little sunlight, the grand scheme of things, between Zemsky and former state agency/Canalside CEO powerbrokers Larry Quinn or Jordan Levy. They’re all well-off, well-connected political and business bigshots. Zemsky gets the high fives from Esmonde despite the fact that Larkinville is a suburban office park surrounded by a sea of surface parking. Quinn now fecklessly moistens a Paladino-aligned seat on the school board, and Levy has gone on to help kickstart the successful incubation and promotion of entrepreneurs and startups through 42 North. In Esmonde’s world, Levy’s philanthropy and activism merit no mention despite the fact that they strike at the heart of Buffalo’s long dilemma: industry and manufacturing are largely gone, so now what?

Bass Pro: Plans A-C

At first, Bass Pro was going to be the anchor of an Inner Harbor entertainment district, and the plan was for it to be sited in a renovated Memorial Auditorium. Over the course of years, we lived through a meaningless memorandum of understanding (MOU), debates about the use of public subsidies, then-County Executive Joel Giambra refusal to sign the MOU, then changing his mind, then whether we should use one-shot tobacco money, and whether sales tax rates should be hiked. We made it through Governor Pataki’s creation of the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation at Brian Higgins’s urging, the naming of Canalside and the first 30-day deadline for Bass Pro to commit, which turned into a 60-day deadline, which turned into no deadline. For a period of time measured in years, the Bass Pro / Canalside project remained “imminent“. As the NYPA reauthorization moved forward, we reassured that Bass Pro’s secretive executive clique was uniformly and constantly in a state of perpetual excitement of the deal being done.

January 17, 2007 was supposed to be the final day for Bass Pro to commit to the Aud, but it never happened. The whole fiasco became emblematic of Buffalo’s pathetic pursuit of silver-bullets to rejuvenate itself. As the Aud project fizzled, the city decided instead to rip down the unused and largely unusable Aud. Bass Pro and the ECHDC then turned their attention in early 2007 to the Central Wharf, right down to the imminent- signed – deal and flyover animation.

At the top of list is the historic Central Wharf, across Scott Street from the Aud, directly on the Buffalo River. The approximately 1.5-acre site, adjacent to the recently rewatered Commercial Slip, is being eyed for a store that would resemble an original, early 1800s commercial structure.

Suddenly the local preservationist cliques went to war, threatening lawsuits even before any plan had been finalized or formalized. ECHDC then-Vice Chairman Larry Quinn led the pro-Bass fight as opponents of the nascent plan polluted the process with catchy, knowing buzzwords and false accusations of taxpayer giveaways, suburbanization, all summed up best by the word, “big box“. Quinn took the opposition on. Never mind that the structures that once sat on the Central Wharf were, in fact, big boxes.

Reasonable and unreasonable discussions galore were had about this downtown shopping mall. In any event, the Bass Pro on the Central Wharf idea was dead before it was ever born, a victim of propaganda and demagoguery as “chain stores” replaced “big box” as our civic bête noire. It also died thanks to the hubris and arrogance of the people entrusted with power, money, and leadership. Quinn had set forth the central wharf plan as a fait accompli, and set about doing what he does best – proving himself to be the smartest guy in the room, even when he isn’t.

Throughout the process, people wondered why ECHDC wouldn’t simply put in utilities, cobble the streets, and auction off parcels with very stringent use and design guidelines. Why isn’t that being done now? Could it be because people want to put their fingers on the scales when it comes to who gets the development deals? Maybe they can hire Alain Kaloyeros to handle the RFPs.

But Bass Pro was the project that wouldn’t die. When Quinn’s big box on the wharf failed, ECHDC pivoted in October 2007 to a plan C – a new-build on the site of the demolished Aud. Discussion ensued, and by 2008, Bass Pro was pleading with Buffalo to hurry things up, already. The project was up for public comment and was going to cost $500 million. Suddenly we had a “pre-development agreement”, which roughly translates as “nothing”, then more nothing, and more nothing, and angry nothing, all going through three governors in six years, generating little more than news reports, renderings, and animations.

By 2010, Bass Pro was a hilarious afterthought about which no one cared anymore. While Buffalo was awash in “fish or cut bait” jokes, people were still debating what to do down there. On July 21, 2010, Brian Higgins imposed a 14-day ultimatum for a final agreement with Bass Pro. Next came a lawsuit, before Bass Pro finally put everyone out of their misery and announced it was never coming to Buffalo, ever.

In the interim, Bass Pro’s main competitor, Cabela’s, opened a store on Walden Avenue in Cheektowaga. Just this year, Bass Pro acquired Cabela’s, meaning western New York will have its Bass Pro after all. The whole protracted drama was bookended by Masiello and Pataki donning flannel on the one hand, and Carl Paladino invoking Marx and ACORN on the other, and a lot of typical failure in between. Reading through my WNYMedia.net commentary from 10 years ago, we were reasonable when necessary, snarky when not. We were hopeful, skeptical, informed, cynical, interested, and offered the community a forum to debate the whole thing. The conclusion? When it comes to discussion of development in Buffalo, don’t bet against the cynics.

Canalside After Bass Pro

Since that time, ECHDC pivoted to the “lighter, quicker, cheaper” “placemaking” alternative to development. In 2011, this led to the historic opening of “Clinton’s Dish”.

picture shack pictures

It’s all very nice, but ultimately placemaking is a scam. The group of people who demanded the Canalside “pause” also persuaded ECHDC to retain the services of Fred Kent from the Project for Public Spaces (at public expense), in order to explain how benches and triangulation would solve all the problems. As a result of this extended delay, we have literally seen the Webster Block go from asphalt eyesore to HarborCenter. Meanwhile, Canalside has the nice replica canals used for summertime and wintertime recreation, some temporary structures, and grass. We have the ice bikes, we have the truss bridges, we have Shark Girl, and we have the boardwalk.

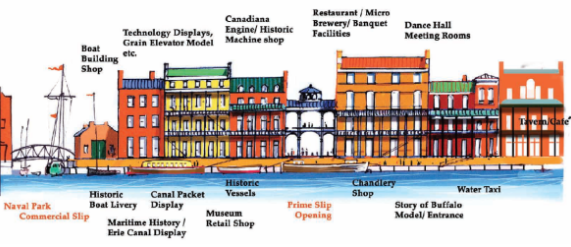

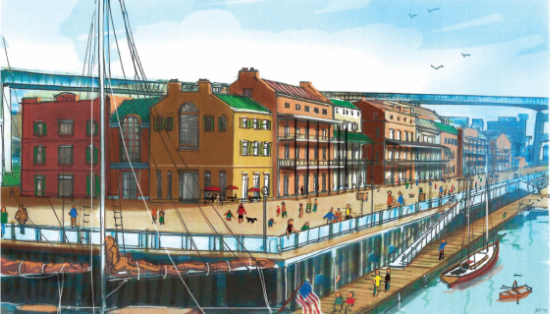

But this is all a betrayal of the original promise of Canalside. Indeed, the very people who vehemently opposed the Bass Pro “big box” on the Central Wharf in 2008 demanded that ECHDC instead follow the 2004 Master Plan. OK, fine – they won and Bass Pro went away. So, when do we get this?

More to the point, when the Buffalo News reports on the new toilets and lawns, why aren’t the 2004 Master Plan proponents opposing that as strongly as they did the Bass Pro Central Wharf idea? Far be it from me to suggest that we should court some new big box or chain store. But when we take visitors down to Canalside, everyone agrees that it’s just great; everyone loves to take a selfie with Shark Girl, and do the handful of other things available. People enjoy that its “flexible lawns” can be used as a concert venue. But it wasn’t supposed to be just that. It was supposed to be more – something not too dissimilar from, say, Boston’s Faneuil Hall Marketplace area. Placemaking enthusiast Mark Goldman had this to say to Donn Esmonde in 2011,

“It is not just people having picnics, it is good economic-development strategy,” Goldman added. “You start small, and it snowballs. By next summer, you’ll see private businesses lining up to come down—instead of asking for big, fat subsidies.”

Lighter, quicker, cheaper. Already, it’s working

It’s 2016. Five years later, there are no “private businesses” lined up “to come down”. It is, alas, “just people having picnics”. So what are we discussing now? Toilets.

In March, the “Buffalo Waterfront Heritage Coalition” had a great idea, but we never heard more about it.

This works! It’s waterfront-y and heritage-y! This truly reflects what the Central Wharf looked like during its industrial heyday. So, where is it? When will ECHDC let this thing just happen?

Not anytime soon, it appears.

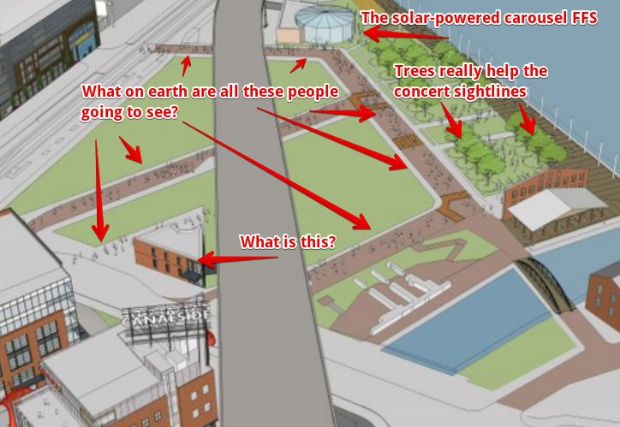

But we don’t have Bass Pro, we don’t have Explore ‘n More, and we don’t have any major construction at Canalside; we instead have a major announcement of permanent bathrooms that will, presumably, be unlocked and available for use at all hours. We will get the solar powered carousel championed by former Erie County Legislator Joan Bozer. Also,

… the summer concerts [will be] relocated to a permanent performance stage on the Central Wharf.

On the backdrop of the stage will be a facade depicting the 19th century Union Steamboat Company. And facing it will be a pavilion that’s a ghosted structure meant to recall another 1850s-era canal district building. The building will serve as a shelter for shade, activities and entertainment.

Permanent stage? Ghosted replica facade? When did the 2004 Master Plan turn into this?

Who loves the ill-conceived jumble of disused lawns and a “permanent stage” with a ghosted faux-cade? Mark Goldman, the guy who strong-armed the ECHDC to hire Fred Kent and gave us “placemaking” in the first place.

Who doesn’t love seeing a “heritage-based” stage show on a windy 10 degree F day in February? What happened to this?

Transforming the Central Wharf at Canalside into some sort of permanent concert venue is a devastating mistake. If anything, it cements as permanent and perpetual a “flexible lawn” with Adirondack chairs, which was supposed to be a “placemaking” stopgap. When you look at the renderings from the 2004 there is a noticable absence of green space. Because it’s a city and this is its downtown. If you look at the renderings from the Waterfront Heritage Coalition, there are no big empty lawns. Instead of Buffalo’s Faneuil Hall, we’re planning a summertime concert venue/lawn-cum-frozen wasteland exposed to lake winds. We already have a summertime waterfront concert venue – disused though it may be – at LaSalle Park.

Buffalo is now in its second decade waiting for something more permanent to be done around Canalside. Look at the 2012 renderings from Brian Higgins’ Flickr account shown above – see the people? They’re there because there are things to do. Not just selfies and skating, but food, drinks, shopping, art, and crafts. Maybe offices, apartments, and hotels. The possibilities are exciting, but not as long as we’re stuck with ghosted facade stages that placate the naysayers. There are no implements being used right now to construct anything seen in the renderings shown above. Canalside’s promise remains years away.

If ECHDC is satisfied with satisfying Mark Goldman, that’s not good enough. It has the power, money, influence, and ability to do something with these parcels right now. Subdivide them and make them ready for development. Sell them. Enough with the “designated developer” nonsense to reward campaign donors. It can grow organically – it doesn’t need to be a Benderson project or a Ciminelli project or an Ellicott project. It can be all or none of those.

Let’s aim higher than toilets, lawns, police substations, and bullshit phony stages. We can do better than this, and it doesn’t even take much imagination to do it. Canalside is better than just a venue for the Buffalo News to take 200 pictures for a Buffalo.com “Smiles at” clickbait featurette. We’ve been patient. Give us what we’re waiting for.